In the lexicon of structural engineering, glory is almost exclusively bestowed upon the visible. We celebrate the soaring cantilevers, the slender skyscraper silhouettes, and the audacious spans of bridges. Yet, these monumental achievements of concrete and steel are entirely beholdan to an unseen, uncelebrated, and far more complex counterpart: the foundation. And when superficial soils prove weak, compressible, or unstable, the structure must call upon its hidden superpower—the deep pile foundation.

A pile is not merely a “post in the ground.” It is a sophisticated geotechnical element, engineered to solve the fundamental problem of load transfer through incompetent strata. It is the indispensable component that contends with the profound uncertainties of the earth. For the professional engineer, understanding the multifaceted role of piles is to understand the very “art of the possible” in modern construction. Their function extends far beyond simple vertical support, encompassing a spectrum of capabilities that actively resist the most complex forces that nature can muster.

The Fundamental Mandate: Bypassing Uncertainty

The primary, and most widely understood, function of a pile is to act as a load-transfer conduit. Superficial soils—such as unconsolidated alluvium, soft marine clays, or uncompacted fills—are often characterized by low bearing capacity and high compressibility. To found a heavy structure on such materials is to guarantee catastrophic failure, or at best, debilitating differential settlement.

The end-bearing pile solves this problem with elegant brutality. It acts as a structural column, driven or drilled through the weak layers until its tip is seated firmly upon a competent, high-capacity stratum. This could be bedrock, such as the Manhattan Schist that famously supports New York’s skyline, or a dense, over-consolidated layer of sand or gravel. In this application, the pile’s “superpower” is its ability to seek out and engage this deep, reliable strength, effectively ignoring the liabilities of the overlying soils. The structural loads are channeled directly to this unyielding layer, ensuring stability and minimal settlement for the life of the structure.

The Art of Friction: Harnessing the Soil-Structure Interface

But what happens when bedrock is economically unreachable, lying hundreds of meters below? This is common in vast deltaic regions, such as in New Orleans, Bangkok, or Shanghai. Here, the pile must deploy a more subtle, yet equally powerful, capability: skin friction.

A friction pile derives its capacity not from its tip, but from the cumulative shear resistance developed along the entire length of its embedded shaft. The pile and the surrounding soil engage in a composite, symbiotic relationship. The load from the superstructure is shed incrementally into the soil mass as a shear stress at the pile-soil interface.

This is a far more complex analytical challenge, requiring a deep understanding of soil mechanics and in-situ soil properties ($K$, $\delta$, and $c_a$). A group of friction piles behaves as a single, composite block, engaging a massive volume of soil. The design must be optimized; too short, and the piles will fail in shear. Too long, and the cost becomes prohibitive.

This power, however, has a critical vulnerability: the phenomenon of “negative skin friction” or “downdrag.” If the soils surrounding the pile are still in the process of consolidating (due to their own self-weight or a nearby surcharge), they will “drag” the pile downwards. This downdrag is not a resistance; it is an additional, and often enormous, load applied to the pile, which can lead to failure if not properly anticipated in design.

The True Superpower: Resisting the Invisible Forces

While vertical support is their most common function, the true “superpower” of piles is revealed in their capacity to resist forces that are anything but gravitational.

1. Resisting Uplift (Tension Piles) A structure does not always push down. For tall, slender towers, high wind loads can create an overturning moment that results in a net uplift force on the windward-side foundations. For structures with deep basements extending below the water table (e.g., underground parking or transit stations), hydrostatic pressure creates a massive, constant buoyant force. In these scenarios, the pile foundation acts as an anchor. It engages the soil in tension (a combination of skin friction and self-weight) to hold the structure down, preventing it from heaving or overturning.

2. Resisting Lateral Loads In many of the most challenging engineering environments, the dominant design forces are horizontal.

Offshore Platforms: These structures must resist the colossal, cyclic forces of waves, wind, and ocean currents. The large-diameter “battered” (angled) piles that form their foundations are designed as massive, laterally-loaded cantilevers embedded in the seabed.

Bridge Piers: Bridge foundations in waterways must contend with horizontal forces from ship impacts, river scour (which removes soil and unsupported pile length), and ice flow.

Seismic Design: In an earthquake, two things happen: the ground itself moves, and the superstructure’s mass creates an inertial “base shear” force. Piles are critical in resisting these lateral loads, acting as ductile “fuses” that can deform and dissipate energy. Furthermore, in liquefiable soils, piles are often the only solution, transferring the load to a stable stratum far below the liquefaction-prone layer, preventing a total loss of bearing capacity.

The Hybrid Solution: The Piled-Raft System

In modern geotechnical practice, the approach is rarely a binary choice between a shallow raft or a deep pile foundation. The piled-raft foundation is a highly optimized, hybrid system that leverages the strengths of both.

In this configuration, the raft foundation is designed to rest directly on the soil and is strategically augmented with piles. The raft and the piles work in concert. The raft itself provides a significant portion of the bearing capacity, while the piles—often placed in key locations, like under core walls—act as “settlement reducers.” This innovative approach controls the total and, more importantly, the differential settlement across the structure. It is a more economical and resilient solution, demonstrating an advanced understanding of load sharing between the structural elements and the soil mass.

The Invisible Mandate: Installation Integrity and Verification

A “superpower” is useless if it fails to activate. The hidden nature of piles presents their greatest practical challenge: quality assurance. A pile’s design capacity is entirely contingent on its installation.

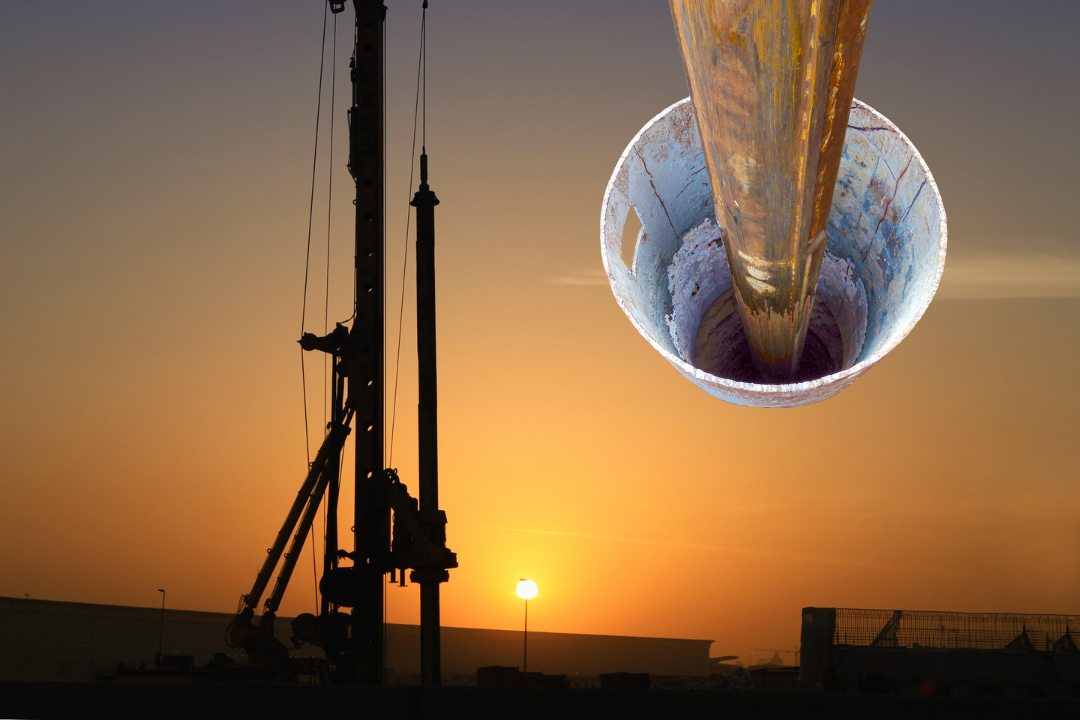

Bored Piles (Caissons): These are constructed by drilling a shaft, placing a steel reinforcement cage, and filling it with concrete. The risks are immense. The borehole can collapse, the base may not be adequately cleaned (a “soft toe”), or concrete placement can be flawed.

Driven Piles: These (steel, concrete, or timber) are hammered or vibrated into the ground. The challenge here is driving them to the correct depth and resistance without damaging the pile’s structural integrity.

Because the final product is invisible, a robust verification protocol is non-negotiable. This is the realm of sophisticated diagnostics:

High-Strain Dynamic Testing (PDA): A pile-driving analyzer is used during installation to assess the pile’s capacity and integrity in real-time.

Low-Strain Integrity Testing (PIT): An acoustic-based method used post-installation to detect major cracks, voids, or “necking” in the pile shaft.

Crosshole Sonic Logging (CSL): Used for bored piles, this involves sending ultrasonic pulses between tubes cast into the pile to create a 2D “image” of the concrete quality.

Static Load Testing: The gold standard, where a pile is physically loaded (often to 200% or more of its design load) to create a definitive load-settlement curve.

Conclusion: The Indispensable Element

Piles are far more than static, load-bearing “stakes.” They are dynamic, multi-functional, and highly engineered components that form the critical interface between the superstructure and the complex geological medium. They are the elements that manage uplift, resist lateral shear, and artfully distribute loads through friction or bypass weakness to find strength. They are, in every sense, the unseen superpower that makes modern infrastructure resilient, safe, and, in many of the world’s most challenging environments, possible at all.